The international student recruitment challenges that are pushing China back up the priority list for UK universities and why, for many of them, success will be harder to achieve this time around.

Universities in the United Kingdom are under pressure from falling international student numbers. Data from Enroly, an admissions services platform widely adopted by UK HEIs, indicated that overseas enrolments have fallen by around one third in the January 2024 intake compared to January 2023.

The sharp fall was driven by a big drop in postgraduate numbers from India and Nigeria. Across all levels of degree, the number of Confirmation of Acceptance of Studies – the formal document issued by universities to enable students to apply for a study visa – fell year-on-year by 33% from India and by 70% from Nigeria. A significant currency devaluation also had a role to play in the decline in Nigerian numbers, but new restrictions on dependants of taught postgraduate students joining them for the period of their programmes is the main factor.

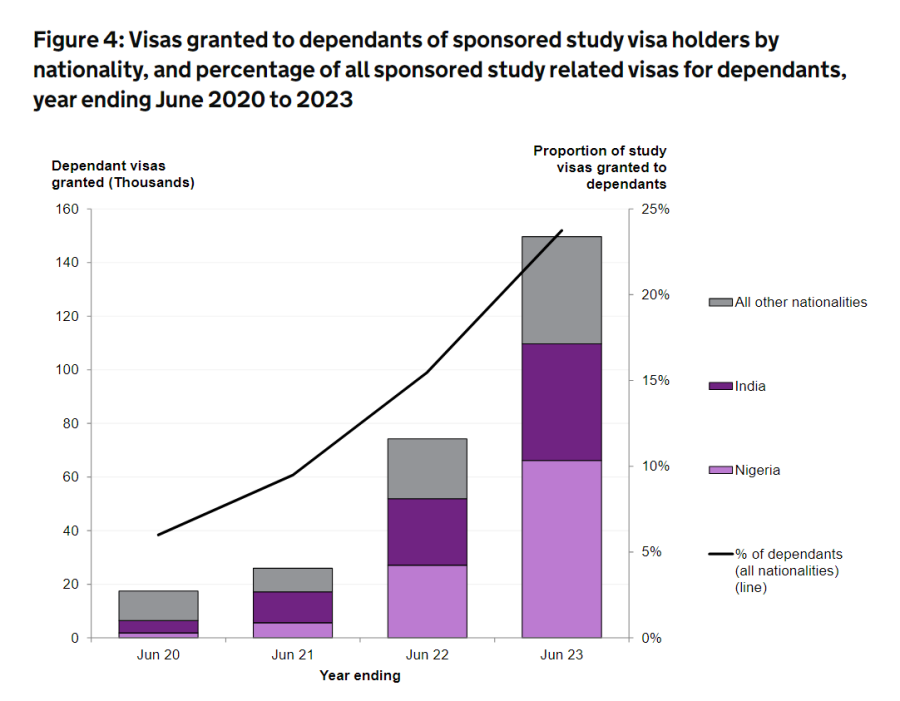

The chart (labelled Figure 4) below shows how the number and proportion of study visas granted to dependants had risen strongly until June 2023, with Nigeria and India being the source markets with the largest volumes. Changes to the rules for granting visas to dependants of students were announced in May 2023, and took effect in January 2024.

Source: Home Office, Why to people come to the UK? To study (Updated 14th November 2023)

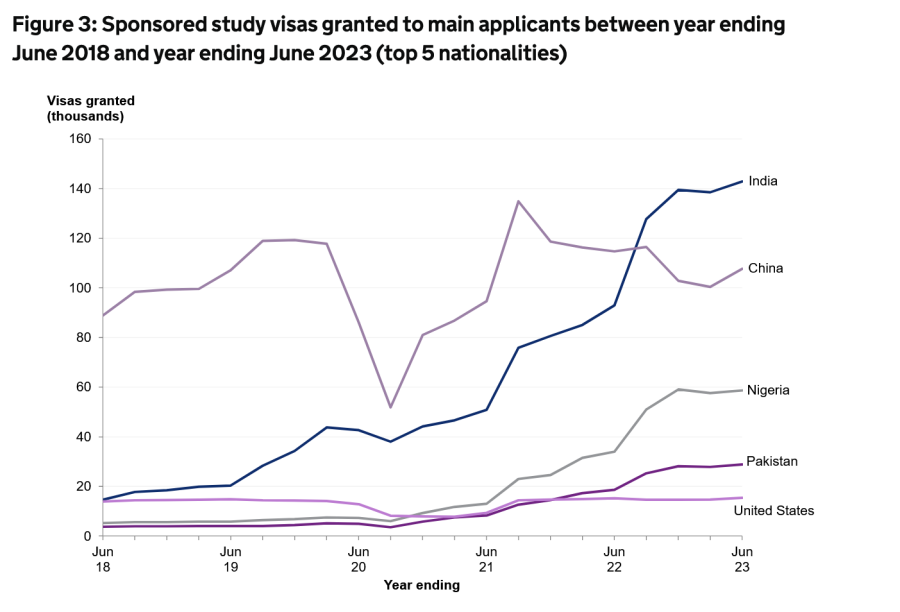

UK universities had previously enjoyed very strong growth in the past few years from both India and Nigeria, as seen on the chart (lablled Figure 3) below. A change in policy has impacted the ability of many dependants of international students to secure a visa to accompany them for the period of their studies. Universities fear that possible restrictions to post-study work visas, known as the Graduate Route, currently being considered by the Migration Advisory Council (MAC), will further erode their pulling power. Such a major change would further impact student flows from several key source markets. However, students from India, represented 44% of users of post-study visas in 2023, with just over 50,000 of them granted leave to remain via the Graduate Route.

Source: Home Office, Why to people come to the UK? To study (Updated 14th November 2023)

Auspicious opportunities

With numbers taking a downward turn from India and Nigeria, China will again come to the forefront of focus for many of the UK’s universities.

In her insightful 2023 book, The New China Playbook, Beyond Socialism and Capitalism, Keyu Jin writes that ‘according to the Chinese Ministry of Education, of the five million students who completed their studies abroad between 2000 and 2019, around 86 per cent returned to China.’ Deng Xiaoping, the Chinese leader who did so much to shape the country’s rapid development in the late 1970s and 1980s, introduced policies that allowed Chinese youth to travel overseas for higher education. In doing so he rightly envisaged that many of them would stay abroad for some time, writes Jin. He held the long view that this would still be a positive outcome for China’s economic development. Nowadays, the fact that so many of its students return to their home country, makes China a safe bet for UK policy makers concerned about study visas being a backdoor route to immigration.

Although now the second largest source market, China’s importance to UK universities is not in doubt. But many universities have struggled to recover their previous volumes after the Covid pandemic, despite the initial bounce after the extended period of lockdowns in China ended. Other universities are keen to manage the risk, created by over-exposure to China, that impacted them during the Covid years.

In the Chinese zodiac, the dragon year brings ‘auspicious opportunities and exciting advancements for all.’ The dragon ‘is considered a celestial and divine creature, with the ability to control natural elements such as wind and water.’ Can UK universities capitalise on the dragon year’s good fortune? And to what extent can they influence student flows from China anyway?

A Chinese new year dragon, Royal Albert Dock, Liverpool, February 2024

A two tier system

Times Higher Education recently published a short news story under a headline, quoting consultant Vincenzo Raimo, proclaiming that international student recruitment from China is ‘getting harder’. The article itself went on to describe a small 3% increase in applications via UCAS by the January deadline for the 2024-25 academic year. According to Mark Corver of dataHE, the market has bifurcated into a two tier system, with recruitment success in China highly reliant on a university’s research profile and ranking. Universities outside the Russell Group of UK elite universities, especially those lower down in the league tables, were often previously able to drive good numbers from China. Now they are finding the market much tougher than they did pre-pandemic.

Conversely, many universities at the top table will have no problem in achieving high volumes, but their goal is to avoid the financial risk that surfaced in the pandemic due to a ‘super-dependency’ on China. Building on the Times Higher Eduction article, and quoting the comments in it from Raimo and Corver, there follows a summary of the dynamics at play for UK universities competing in the China student recruitment landscape, with additional analysis and commentary.

“one very striking aspect of this demand from China is the high and increasing focus on a small set of very selective research-intensive universities such as the Russell Group” (Corver)

That Chinese students, and their parents, focus on high ranking universities is not a new phenomenon. Current data for international student flows to specific universities in the UK is woefully lagged. HESA, the higher education statistics agency, part of Jisc, proclaim themselves as the data experts for the UK sector. The latest data published for overseas student volumes relates to the 2021-22 academic year. Under normal circumstances, the 2022-23 data would be published by now, but even that would not be that useful in understanding current trends.

An analysis of this data illustrates the concentration of students from mainland China. There were almost 528,000 full-time non-European Union international students enrolled in UK higher education institutions supplying data to HESA in 2021-22, out of a total enrolment of 2.27 million. 494,350 non-EU international students of the 528,000 were enrolled at one of the 121 universities ranked by the Guardian newspaper in its 2021 UK best universities league table (Oxford was ranked number 1, Bedfordshire at number 121). Of the 494,000, the number from mainland China was 143,545 or 29% of the total.

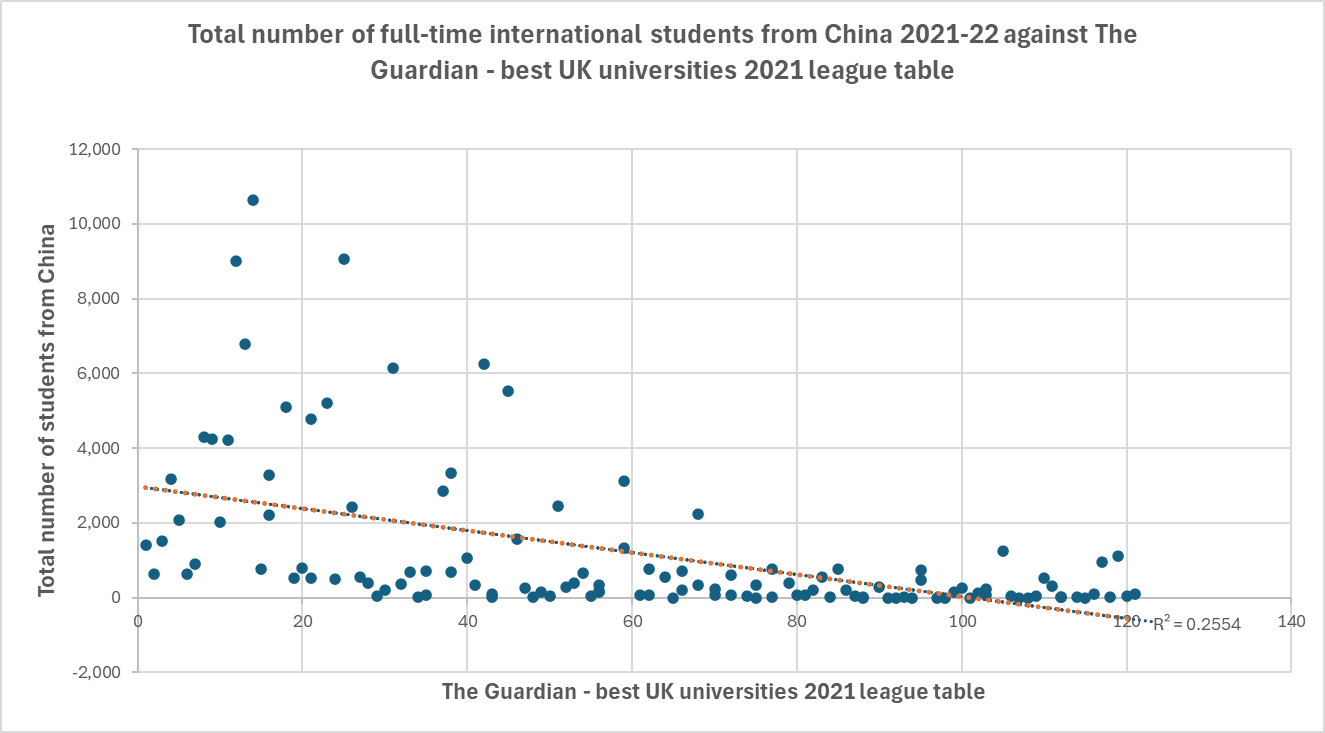

The chart below shows a basic overview of Chinese full-time students enrolled by a university’s position in the 2021 Guardian league table. The goodness-of-fit line has an R-squared of 0.255 meaning that 25% of the variance in student volumes are explained by league position* (see footnote).

A basic analysis, showing a moderate correlation: more work is needed over multiple years and rankings

Of the 24 universities which are members of the elite Russell Group, only five had a percentage of full-time students from mainland China, compared to their total full-time non-EU international 2021-22 enrolments, of less than 40%: the University of Oxford (25%), the University of Cambridge (30%), Queen Mary, University of London (32%), London School of Economics and Political Science (32%), and the University of Exeter (33%). Four had a proportion of over 60%, with the University of Southampton weighing in at 72%. Strikingly, 105,000 full-time students from China attended a Russell Group university, representing 51% of the full-time non-EU international total students enrolled in the 24 member institutions. 10,635 from China attended University College London alone. If, as Corver suggests, there continues to be an increasing focus on select universities, it will be interesting to see the numbers in the 2023-2024 data, whenever HESA is able to publish it.

“Those lower down the rankings will, however, increasingly have to look elsewhere for their international students.” (Raimo)

Some lower-ranked, post-1992, and non-research led universities, did have good numbers of full-time Chinese students in 2021-22. University of Westminster (ranked 117 in the Guardian’s 2021 UK university league table), and De Montfort University (119) registered 955 and 1,120 respectively. Coventry University recorded 2,425 , although also had the benefit of being upwardly mobile in the rankings (26). Specialist provider, the University of Arts London registered 5,530, 57% of its international non-EU total, underlining the popularity of art and design courses in China.

Articulation and progression agreements with partner universities are credited for the success of universities like Westminster and De Montfort – both have long-standing and active initiatives in China, demonstrating the possibilities of recruiting students to their similarly low-ranked peers. Whilst it is true that most post-1992 universities do not have anywhere near this level of success in China, it appears to be the case that Westminster and De Montfort continue to see it as a productive source market, despite their league position. It is possible for such universities to do well in China, if a targeted long-term strategy is in place and well-executed.

Chinese students’ families “are also increasingly becoming cost conscious and looking for value for money – both in terms of costs of study and employability back home – and the UK is increasingly seen as an expensive option, especially compared with those closer to home options” (Raimo)

There is intense competition for international students amongst proactive institutions across an increasing number of destination countries, whether situated in the traditional international education powerhouses of the United States, Canada, Australia and the UK, or in emerging destinations in Europe, Asia and elsewhere. The UK government, having promoted growth in international student numbers, is now fixated on cutting net migration numbers, in which they bizarrely count students intending to be in the UK for only the duration of their degree programmes, before returning home.

In a December 2023 UCAS published a report seeking to understand the motivations and views of Chinese undergraduate students in the UK entitled Global Insights: What are the experiences of Chinese students in the UK? UCAS projects a growth to 50,000 undergraduate applicants from China by 2030, a significant increase from the 33,195 in 2023, even whilst noting that ‘some commentators are suggesting that the UK may be close to ‘peak China.’

One section of the report focuses on the differences in the experiences of Chinese undergraduate students in the UK, against their expectations. It finds that ‘72% find their living expenses to be higher than expected’. Despite this, 91% are extremely likely or likely to recommend the UK as a study destination, with the quality of the course meeting or exceeding expectations in 92% of cases. Indeed, 73% are considering to stay in the UK after completing an undergraduate programme. These findings shine a very positive light on the attractiveness of the UK, in the face of heightened competition from other destinations.

A shortage of graduate employment opportunities in China, following economic challenges and government legislation to constrain the financial, gaming, and technology sectors, means that Chinese students are putting even more emphasis on the job prospects that a university degree can lead to. The report advocates greater support for international students on their employability, and the measurement of graduate outcomes. The value of graduating from a high-ranked university is again emphasised, with Shanghai now offering a hukou – a hard to obtain household registration document necessary for people hailing from elsewhere in China to live and work in the metropolis – to those who have studied in a world top 100 institution.

Overall, the report points to a positive outlook for China as a future source of growth in international student numbers. Geopolitical tensions are always a looming threat to be wary of, although the probability and impact is hard to anticipate or predict. Whilst economic growth in China remains sluggish, driven in part by the crisis in the property market, a further rise in the Chinese middle class, and the ongoing attractiveness of an overseas education, is predicted to transcend any short-term volatility in student numbers.

President Xi Jinping: searching for economic recovery

Conclusion

With pressure on numbers from India and Nigeria, UK universities are once again turning their attention to China as a source of growth for international students. Growth prospects remain strong over the medium and long term. However, it is the high-ranked universities that continue to hold a major advantage in the market share battle.

The notable past successes of a handful of post-1992 universities, demonstrate that a clear-headed strategy, and a focus on execution, can deliver good returns for higher education institutions outside the elite Russell Group. Yet it is clear that the lower-ranked universities enjoying success today have had to work hard over a considerable period of time to achieve it. When recruiting students from China, there are no easy solutions. The macroeconomic and geopolticial context may have altered, but the UK’s international education sector has not yet reached ‘peak China’.

*Footnote: Further analysis is needed as the Guardian annual league table is only one method of ranking universities, and not the most commonly referenced one in China. Indeed in the 2021 Guardian table, 8 of the elite Russell Group universities were actually ranked outside the top 25.